Truman Capotes unhappy ending | PBS NewsHour

While seated in a London theater recently to watch a performance of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” I was reminded of the close relationship between the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Harper Lee and the fabulous writer Truman Capote.

Friday would have been Capote’s 98th birthday, but he died a month shy of his 60th year — on Aug. 24, 1984 — a victim to the stranglehold of drug addiction and alcoholism.

While Capote was working on the reporting for the work that would become “In Cold Blood” – his “nonfiction novel” as he liked to call it – in 1959, Lee joined him in Holcomb, Kansas, and helped him take notes and interviews.

Lee’s novel, “To Kill a Mockingbird,” came out in 1960. Her character Dill, of course, was based on Capote, a fatherless boy parked in Monroeville, Alabama, by his feckless mother to be raised by relatives, especially during the time period that served as the basis for Lee’s now classic novel. Capote’s aunt was a neighbor of Amasa C. Lee—Harper Lee’s father and the basis for Atticus Finch.

He underwent numerous stays at rehabilitation clinics, but each time he was released, he went farther into the abyss.The novel’s success became a great source of jealousy for Capote and their relationship was strained after its publication. Capote, on the other hand, didn’t publish his masterpiece until 1966, after the murderers of the ill-fated Clutter family, Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, were executed.

“In Cold Blood” — a literary landmark of the 1960s — did not win the Pulitzer Prize or the National Book Award, to Capote’s lasting disappointment. Nonetheless, the book was a massive bestseller and elevated him to the pantheon of America’s most famous writers. He celebrated his success by throwing the famous Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel in November 1966, where everybody who was somebody clamored to be invited.

READ MORE: The day Judy Garland’s star burned out

Capote was born Truman Streckfus Persons in 1924, to a 19-year-old Lillie Mae Faulk and a salesman named Archulus Persons. His parents divorced when he was only 2 and he endured a lonely childhood that was made slightly better by pencil (he preferred the Blackwing 602 with a replaceable eraser) and paper. He started writing short stories when he was about 11 and never really stopped. A perfectionist, he was known to spend an entire day searching for the right word or phrase to adorn his luminous prose.

In 1932, his mother married a Cuban-born bookkeeper named Jose Garcia Capote, who adopted the boy and gave him a new surname. While in New York and later Greenwich, Connecticut, he attended several preparatory schools, but never went to college, instead wangling a job as a copyboy for the art and cartoon department of The New Yorker. Known for embellishing details of his life, legend has it that if he did not like a particular cartoon, he would throw it or file it away, or drop it behind a desk. His stint at the magazine didn’t last too long – Capote (reportedly unintentionally) insulted the poet Robert Frost at a poetry reading in Vermont, and Frost complained to the magazine’s founder and editor, Harold Ross.

From there, he embarked on an exciting life of writing and socializing with everyone who was a literary or society name—or about to become one— during the 1950s and ‘60s. He published short stories in several magazines, began a permanent feud with Gore Vidal—each telling awful stories about the other— enjoyed a close friendship with Tennessee Williams, and partied with socialites ranging from Lee Radziwill (the sister of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis), Gloria Vanderbilt, Nancy “Slim” Keith and Barbara “Babe” Paley (the wife of CBS founder and television mogul William S. Paley). Along the way, Capote wrote classic novels and essays, ranging from “Other Voices, Other Rooms,” “The Grass Harp” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s.”

Long a heavy drinker and cigarette smoker, by the early 1970s Capote was abusing cocaine, alcohol, tranquilizers, marijuana and other substances. Over that decade, he underwent numerous stays at rehabilitation clinics, but each time he was released, he went farther into the abyss, whether it was dancing all night at Studio 54 or embarking upon disastrous personal relationships with lovers and friends.

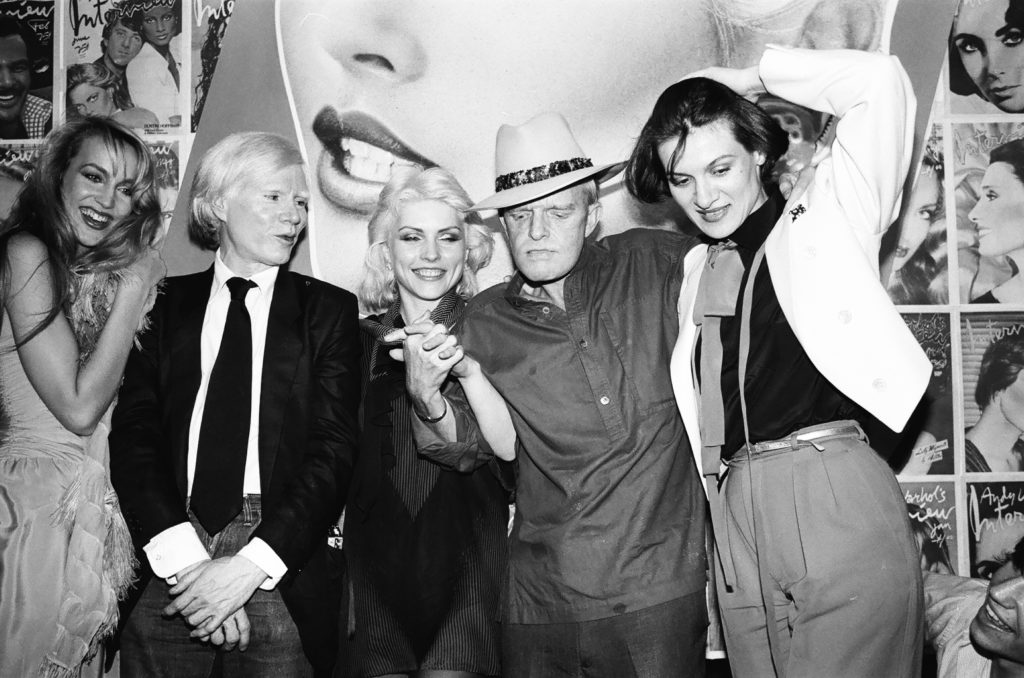

Jerry Hall, Andy Warhol, Debbie Harry, Truman Capote and Paloma Picasso at a party at Studio 54 in June 1979 in New York City. Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images

Before he ruined his beautiful mind, Capote boasted of a razor-sharp memory for everything he heard during an interview, preferring not to write in front of a subject and instead focus entirely on them. In this pursuit, he long planned to become the Proust of the American social elite—the writer who recorded remarkable encounters with the rich and famous, as well as their foibles and adventures. He told his biographer, Gerald Clarke, in 1972 that the novel he was planning would have “every sort of person I’ve ever had any dealings with. I have a cast of thousands.”

The novel, “Answered Prayers,” was never completed. He did, however, publish four of the completed chapters in Esquire magazine between 1975-1976. They outraged his rich friends with scandalous tales told out of school. A chapter titled “La Côte Basque 1965” told an embellished story of a character based on his friend William Paley having one-night stand, and trying to keep it hidden from his wife.

Truman Capote found all the success he craved and then poured it down a drain of addiction and self-harm.Like those elevator lights indicating the car is going down, down, down, Capote’s wealthy friends dropped him. Babe Paley, his best friend, never spoke to him again. Capote was baffled by this response, and never seemed to understand the nature of his betrayal. “I am a writer,” he was said to have moaned, “What did they expect?” His exile led to an even greater consumption of cocaine and alcohol, which, in turn yielded seizures, collapses, public drunkenness and ruin.

READ MORE: Elvis’ addiction was the perfect prescription for an early death

He died in the Bel Air home of Joanne Carson (a close friend and the ex-wife of NBC’s Tonight Show host, Johnny Carson). The death certificate declared the cause as “liver disease complicated by phlebitis and multiple drug intoxication.” True to form, Gore Vidal called Capote’s death “a wise career move.”

Snide comments aside, Truman Capote found all the success he craved and then poured it down a drain of addiction and self-harm. In many ways, the title of his unfinished novel—which is a masterpiece of prose and storytelling even if the rest of the manuscript was either never completed or found—predicted his own unhappy ending. The phrase Answered Prayers, Capote long claimed, came from an epigraph uttered by St. Teresa of Avila – although there is no proof of that attribution. Nevertheless, it fit Truman Capote’s life like a tailor-made suit:

“More tears are shed over answered prayers than unanswered ones.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eYmq6twMdoq6utnZa7bq%2FAqaatnaNiwq%2B0wKmnsmWVo7GqusY%3D